Shadowspect: The Power of Sharing Games

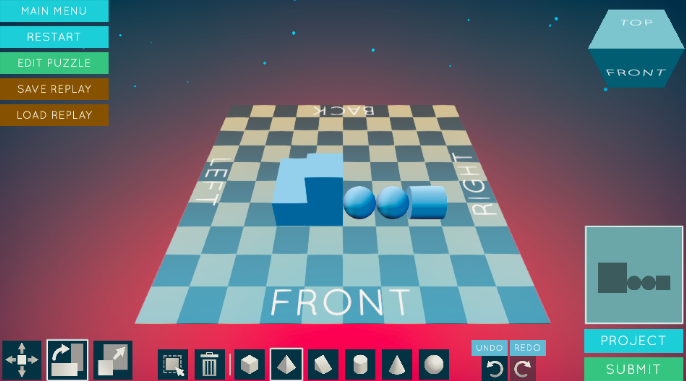

Screenshot from Shadowspect

by Laure Haak

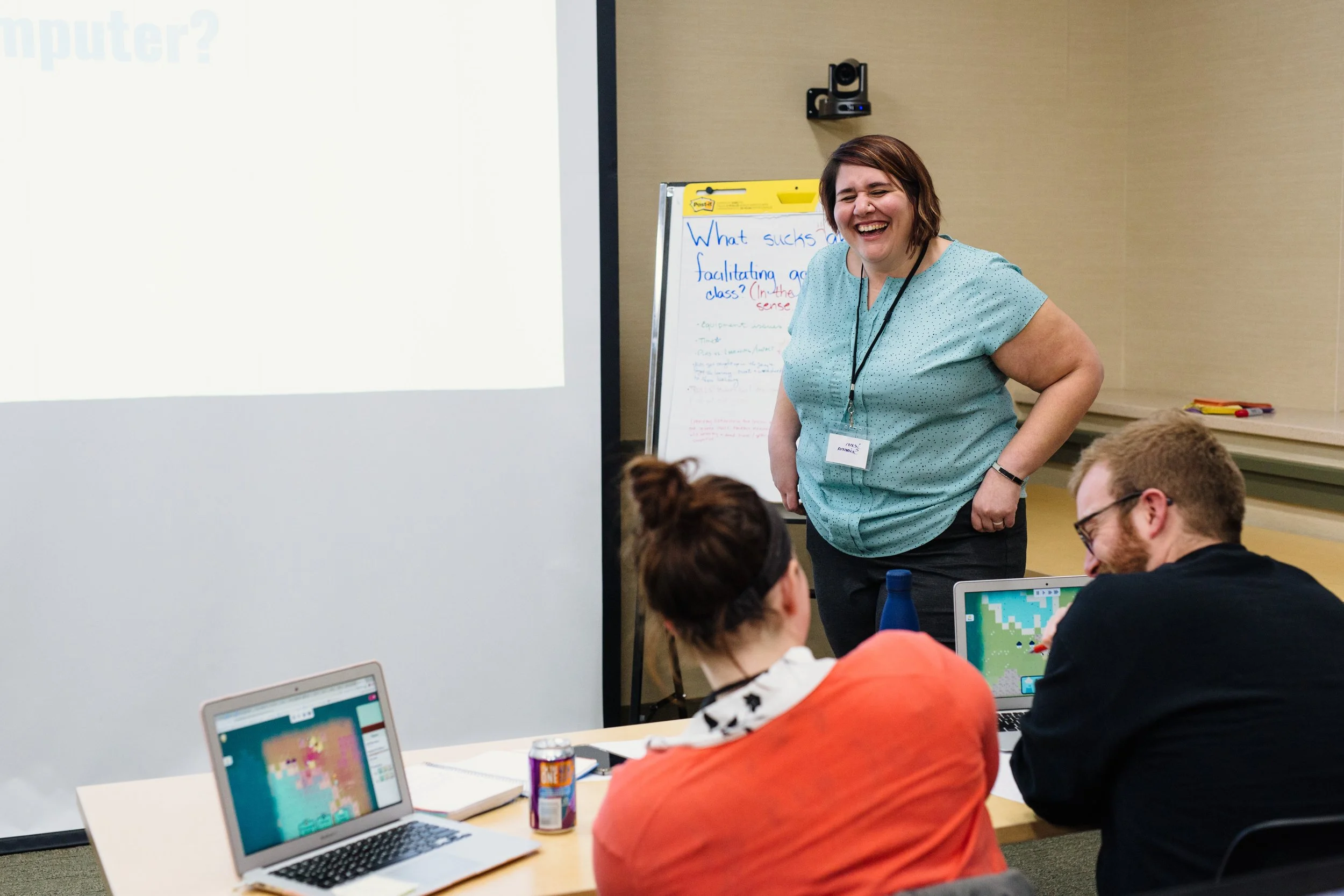

Jenn Scianna is a graduate student at the University of Wisconsin. What got her interested in this path was participating in research around educational games and science classrooms as a middle school teacher, and being frustrated with the ways people were making sense of data and feeding it back to teachers. Her research interest started there, with the idea of developing better dashboards to communicate what students know and understand. This idea has evolved into a focus on learners, understanding playful behavior, and making sense of more complex behaviors.

She started working with Professor YJ Kim on a project investigating how teachers understandunderstood persistence in the classroom. They used Shadowspect, a learning game designed to measure student persistence and spatial reasoning. Most assessments of spatial reasoning used paper-based methods, and show a gender-based difference. What Shadowspect allowed, as a video game, was the ability to test spatial reasoning skills in a different way. This isn’t something teachers often assess in the classroom, and it wasn’t clear what they would do with the information. In addition, since spatial reasoning had been shown in other studies to correlate with students performing well in STEM careers, the research had workforce implications.

YJ Kim is currently a Senior Lecturer at University of Adelaide

Shadowspect research had two primary aspects. One was a co-design process with classroom teachers, previously done by Professor Kim, working in person and remotely using Miro to elicit how teachers think about evidence, assessment, and persistence. And the other was to determinedetermining what information could be obtained using Shadowspect, and how itthat could be represented for teachers in a way that is actionable.

Jenn’s work initially focused on the assessment component, analyzing meeting transcripts. But she needed to connect the teacher interviews with data from the game. She wondered -, how can we createdo you get a system that allows someone who is not a data scientist to access the data and be able to ask simple questions and explore?

At about that time, Field Day was starting to engage with the learning games and educational research community about creating an open games infrastructure, . Wwhere games like Shadowspect could be hosted, instrumented, and game data collected and made available for analysis. So that is what YJ and Jenn did. They worked with the Field Day team to create a data schema that mapped the existing event logging built into the game, loaded Shadowspect into the Vault, a game distribution service that also enables the collection of anonymous player data. At the same time, Shadowspect was also loaded into BrainPop and other distribution services.

Jenn Sciana

“So, even though the main research questions had been addressed in the co-design work, the game lives on,” explained Jenn. “Data are still coming in!” Even better, since Shadowspect was one of the first learning games to integrate anonymous player codes, also from Field Day, there is a “save” state tied to a player - not to the computer they are playing on. That means it is possible to connect player activity over multiple rounds of play in the same game. Which means even richer data over multiple sessions and potentially multiple rounds of play, particularly of interest in the study of persistence.

As with any research project, there are still a lot of unanswered questions. Last summer, Jenn ran a new pilot with undergraduate students to investigate differences between neurodivergent and neurotypical learners. And because Shadowspect was already in existence and previously had passed through IRB, extending the IRB to use Shadowspect to study a new population using the Vault - which also has an IRB - was a seamless process .

Similarly, for with collecting game data. The anonymous player code added an extra layer of protection for participants and also made it possible to connect data between sessions as well as between gameplay and survey data. “We had users and participants attach their anonymous name from the game into their qualtrics survey,” said Jenn. She has also seen other researchers use the Vault to access Shadowspect for their research and teaching.

Jenn has also been working with Field Day on developing new analytics tools, in her case quantitative ethnography. Field Day is exploring tool development using shared data with other researcher teams.

Further Reading

Scianna J., Gagnon D., Knowles B. (2021) Counting the Game: Visualizing Changes in Play by Incorporating Game Events. In: Ruis A.R., Lee S.B. (eds) Advances in Quantitative Ethnography. ICQE 2021. Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol 1312. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-67788-6_15

Kim, Y.J., Scianna, J., Knowles, M.A. (2023). How Can We Co-design Learning Analytics for Game-Based Assessment: ENA Analysis. In: Damşa, C., Barany, A. (eds) Advances in Quantitative Ethnography. ICQE 2022. Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol 1785. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-31726-2_15

Liu, X., Slater, S., Andres, J., Swanson, L., Scianna, J., Gagnon, D., Baker, R.S. (2023). Struggling to Detect Struggle in Students Playing a Science Exploration Game. CHI PLAY Companion '23: Companion Proceedings of the Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3573382.3616080

Metcalf, S., Scianna, J., & Gagnon, D. (2024). Experiences of Personal and Social Immersion in a Videogame for Middle School Life Science. Academic Proceedings of the 10th International Conference of the Immersive Learning Research Network (iLRN2024), 201–209. https://doi.org/10.56198/U6C0WZQ4R

Scianna, J. & Kim, Y. (2024). Assessing Experimentation: Understanding Implications of Player Choices. In Lindgren, R., Asino, T. I., Kyza, E. A., Looi, C. K., Keifert, D. T., & Suárez, E. (Eds.), Proceedings of the 18th International Conference of the Learning Sciences - ICLS 2024 (pp. 1594-1597). International Society of the Learning Sciences. https://doi.org/10.22318/icls2024.608791

This article is part of a series on pilot projects carried out by the Field Day team in collaboration with internal and external partners, to explore the opportunities and benefits of creating shared approaches to learning games, through standards, processes, and infrastructure. This work wa supported by the National Science Foundation, Grant # 2243668